- Home

- Patricia Williams

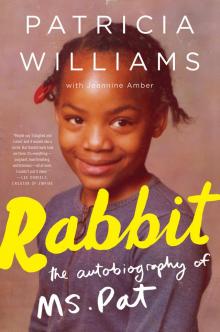

Rabbit

Rabbit Read online

Dedication

To my husband and our four kids, I love you all

Epigraph

Life’s a bitch. You’ve got to go out and kick ass.

—Maya Angelou

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Introduction

Chapter 1: Bear Cat

Chapter 2: Hot Lead

Chapter 3: Struggling and Scheming

Chapter 4: Angel in Leather Boots

Chapter 5: Devil in Disguise

Chapter 6: First Dance

Chapter 7: Love Lesson

Chapter 8: Age of Consent

Chapter 9: Love and Options

Chapter 10: Wife on the Side

Chapter 11: It’s Time

Chapter 12: Baby Formula

Chapter 13: Hustlers and the Weak

Chapter 14: Night Crawlers

Chapter 15: Partners in Crime

Chapter 16: Mama on the Block

Chapter 17: The Breakup

Chapter 18: Aim Higher

Chapter 19: Locked Up

Chapter 20: Hood Wisdom

Chapter 21: Mr. Nice Guy

Chapter 22: Four More

Chapter 23: Letting Go

Chapter 24: Job Readiness

Chapter 25: Eight Minus Four

Chapter 26: Angels

Epilogue

How This Book Came to Be

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

We’d been living in our new place in Indianapolis for only a couple of days when I heard a knock at my front door. I opened up to find a white lady with a big smile standing on my porch, holding a huge chocolate cake wrapped in plastic. “I want to welcome you to the neighborhood,” she said. “So I baked you a little something.”

What the hell? Where I’m from, if somebody shows up at your door with something nice in their hands, it’s probably stolen.

As soon as she left, I went right to my kitchen and called my girlfriend, Ms. Jeanne, back home in Atlanta.

“You ain’t gonna believe this,” I said. “A white lady just made me a cake. You think I should I eat it?”

“Yeah, girl,” said Ms. Jeanne. “White folks always bake you shit when you move in so you don’t break in to their house.”

It turns out, there was a whole lot I had to get used to moving from the hood to the suburbs. Strangers bringing me chocolate cake was only the beginning.

I grew up in the 1980s in the inner city of Atlanta. My mama was an alcoholic single mother with five kids. She could barely read and only knew enough math to play the numbers and count out the exact change to buy herself a couple of bottles of Schlitz Malt Liquor and a nickel bag of weed. Almost none of my relatives, going back three generations, ever graduated high school. Instead, you could say I came from a family of self-employed entrepreneurs. My granddaddy ran a bootleg house, selling moonshine out of his living room; my uncle Skeet robbed folks; and my aunt Vanessa sold her food stamps. With role models like that, what could possibly go wrong?

Even though I came up in the hood, I dreamed of a different life. My fantasy came straight off TV, from my favorite show, Leave It to Beaver. You probably thought I was going to say Good Times, but I didn’t need to watch TV to see black folks struggling. The Struggle was all around me. Compared to how we were living, life on Leave It to Beaver looked like heaven. I was mesmerized by the way the house was so clean and everybody was always smiling and jolly. What I liked most was how Mrs. Cleaver would walk around grinning at her kids like she couldn’t believe her good luck. In my house, my mother would get drunk off her gin, whoop me with an extension cord, call me ugly, and tell me to take my ass to bed. I’d be thinking, How you gonna tell me to go to sleep when it’s ten o’clock in the morning and I just woke up?

I know a lot of people think they know what it’s like to grow up in the hood. Like maybe they watched a couple of seasons of The Wire and think they got the shit all figured out. But TV doesn’t tell the whole story. It doesn’t show what it’s like for girls like me; how one thing can lead to another so that one minute you’re a twelve-year-old looking for attention, then suddenly you end up pregnant at thirteen, with nobody to turn to for help. Folks don’t know about that kind of life because, for a lot of people, girls who grew up like me are invisible. Unless you come to the hood, you won’t see us. It’s easy to pretend we don’t exist.

By the time I was fifteen, I was a single teen mom with a seventh-grade education, no job skills, no money, and two babies under the age of two. My dream was to give my kids a better life, but most days I didn’t even have enough money to buy Pampers. All I wanted was to find a way to get myself and my babies out of the ghetto; I was willing to do whatever it took.

Let me tell you something, moving up in this world is not easy. I worked at factories, gas stations, and fast food restaurants. I’ve hustled and schemed, been shot twice, beaten with a roller skate, locked behind bars with a bunch of junkies and hookers, and nearly got my head blown off for talking shit. Somehow, I survived. Hell, I did more than survive. I got myself and my kids a whole new life.

These days I live with my family in Indianapolis, in a six-bedroom house overlooking a man-made pond with a bunch of ducks swimming around in it. During the day, I do regular suburban-mom-type shit. I go to Walmart, get some lunch at Chick-fil-A, and head over to the gym for Zumba class. Okay, I don’t really do Zumba. I went once, but the teacher was plus size, like me. I kept thinking, Does this shit even work?

At night I hit the clubs. I’m a comic and tour the country telling stories about my messed-up childhood and getting out of the hood. When I started comedy, back in 2004, all I wanted was to make folks laugh. Then I noticed something strange. After almost every show somebody would come up to me and ask the same question, “How did you turn your life around?” It felt like they wanted me to give them some kind of secret tip.

I wish I had a simple answer. But the truth is, it’s a long story. I went from living in an illegal liquor house, to running from the cops, to living in the suburbs with a flock of ducks outside my window. The only way I can explain how it happened is to tell you exactly what went down. So I’m laying it all out in black and white, sharing stories I’ve never told a soul, not even my husband, which reminds me, I should probably warn him about chapter 5.

I used to get embarrassed about the shit I did to survive. I wanted to push it all away and pretend it never happened. But I’ve learned that laughing at my pain helps me heal. I hope my story will inspire you to laugh through your hard times or try something you’ve always dreamed of doing. Maybe you want to get out of a bad relationship, or go back to school, or change your career. Hell, maybe you want to be an overweight Zumba instructor. I don’t know what the hell you lie in bed thinking about at night. That’s your business. All I know is when you finish reading this book I hope you’ll take away the same message that I’ve been carrying in my heart since I was eight years old. It’s a lesson an angel taught me. That angel happened to be my third-grade teacher, who wore badass leather boots and had really good hair. The words she spoke to me all those years ago helped me change my life, and maybe they’ll do some good for you, too. “Patricia,” she said, “I want you to always remember, you can do anything and be anything. All you have to do is dream.”

Chapter 1

Bear Cat

My granddaddy is the only black man I’ve ever met who was never broke a day in his life. He ran an illegal liquor house in Decatur, Georgia, selling moonshine for fifty cents a shot from behind a bar he built himself out of plywood and old scraps of carpet and red leather. Gran

ddaddy’s real name was George Walker, but folks called him Bear Cat or .38 for the two pistols he kept in his front pockets. Granddaddy didn’t believe in banks and didn’t trust anybody, either. He stored his jugs of corn liquor in the living room in a beat-up old refrigerator the color of baby-shit yellow, which he locked up with a thick metal chain. And he stashed his money in a dingy white athletic sock he pinned to the inside of his pants. My brother Dre, who would steal anything that wasn’t nailed down, used to say he’d be one rich muthafucka if he could only get his hands on that sock full of paper. But Dre didn’t want to swipe anything that hung so close to Granddaddy’s mangy old balls.

Most folks were scared to death of my grandfather, not just because he was built like somebody put a human head on a gorilla body, but also because he didn’t take shit from anybody. I remember one night my uncle Skeet was acting a fool while Granddaddy was trying to watch Walter Cronkite on the evening news. The news was serious business to Granddaddy. He liked to talk back to Mr. Cronkite like the two of them were having a real conversation: “What’s wrong with these dumb-ass honkeys?” he’d yell at the TV. “They finna elect a movie star to run this whole gotdamn country. This why a nigga don’t vote!” Or, “Them Iranians some mean muthafuckas. That’s why I don’t go nowhere!” Granddaddy said other than Jesus Christ, Walter Cronkite was the only white man he could trust. Yet here was Uncle Skeet, drunk as Cooter Brown, bouncing on the balls of his feet and shadowboxing right in Granddaddy’s face in the middle of the news.

Granddaddy waited till the commercial break, then he grabbed an old golf club he kept behind his bar and smashed Uncle Skeet right across the jaw, knocking out his front teeth. When the news came back, Granddaddy stopped swinging and sat back down in front of his little black-and-white set, cool as a cucumber, like nothing happened. After that, when the news came on, nobody made a sound.

Back then there were nine of us living with Granddaddy in his big yellow house on Arkwright Place: me, my mama Mildred, Mama’s boyfriend Curtis, my sister Sweetie, and my three brothers. Also, Uncle Skeet who broke into houses and stole shit for a living, and Uncle Stanley who was crippled and slow in the head and had to go to a special-needs school. The bedrooms were in the back of the house and the bar was in the living room, up front. Granddaddy had decorated it with old bedsheets nailed above the windows like curtains, and pictures of Martin Luther King Jr. and Jesus Christ hanging on the wall. The main difference between a regular bar and a bootleg house is that a regular place closes at night and everybody goes home. At Granddaddy’s, folks drank, played spades, shot craps, and hollered at each other until they passed out. On the weekend, it was like a sleepover with the neighborhood drunks. I hated all the noise and commotion. At night I’d go to sleep hoping that I’d wake up and find myself magically living in a clean house where nobody punched each other, no matter how mad they got. But instead I’d get up and find some stranger passed out cold on the living room floor, covered in their own piss and puke. That’s the mess I grew up in. When I was six years old, I thought everybody lived that way.

“Mildred Baby Girl!” Granddaddy called for me one morning, his voice booming through the house. Mama had five children, to this day I am not sure if Granddaddy knew any of our real names. When he wanted us, he’d call us by the order we were born. “Mildred First Boy!” was my oldest brother, Jeffro; “Mildred Baby Girl!” was me. Everybody knew I was Granddaddy’s favorite. When he hollered, I’d come running.

“Help me fix these grits,” he said, when I found him in the kitchen that morning. He was holding a thick metal chain in his hands, because the same way Granddaddy kept his moonshine and guns locked up tight in a fridge in the living room, he also padlocked the fridge in the kitchen. Other kids knew it was mealtime when their mama called them to the table. We knew we were gonna eat when we heard that chain hit the floor.

Granddaddy pushed a chair to the stove and lifted me up so I could stir the pot while he fried up eggs and fatback in the pan beside me. “That’s real good,” he said, looking over my shoulder. “Baby girl, you a natural in the kitchen, musta got it from me.”

Granddaddy’s specialty was homemade cat head biscuits, which were the biggest, fluffiest biscuits you could ever eat, and came the size of an actual cat’s head. He also cooked chicken back, which is 90 percent skin and bones, except for the piece at the end that covers the chicken’s asshole. That piece is 100 percent fat. Granddaddy would cook it in the skillet, drain it on some newspaper, and set it on the table with a bottle of Trappy’s hot sauce. Sometimes I’d pick up a piece of chicken and it would have the news of the day printed all over it.

Everybody used to joke that I stayed up under Granddaddy like a baby chick to a hen, holding onto his pant leg and following him around wherever he went. It’s true. I loved that man with every inch of my whole little heart. Granddaddy made me feel safe. But my mama—she was a whole different story.

“Move out the way so the kids can cut a rug!” Mama hollered, pushing me and my sister Sweetie into the middle of the living room. It was Saturday night and the place was jumping. Anita Ward was singing about somebody ringing her bell on Granddaddy’s little record player, while Mama, drunk as a skunk, yelled for everybody to clear the floor so her two little girls could dance.

Mama was an alcoholic. She drank Schlitz Malt Liquor and Seagram’s Extra Dry Gin, which she called Bumpy Face because of the bumpy texture of the glass bottle. Mama’s drinking was the main reason she didn’t act like any of the mothers I saw on TV. She didn’t help with homework or give us kids advice. She didn’t care about bedtimes, or even where we slept. There weren’t enough mattresses for all the people who lived at the liquor house and it was nothing for Mama to stumble over one of her children sleeping on the floor. She’d just step right over us and keep moving. I don’t remember ever hearing Mama say, “I love you” or “You did good.” In fact, she barely took the time to name her own kids. I have three brothers; one is named Andre and another is named Dre. That’s the same gotdamn name, and those two aren’t even twins.

In the living room, Mama turned up the music.

You can ring my beeeeeeell, ring my bell

Ring my bell, ring-a-ling-a-ling

“C’mon now,” she said, pushing folks out of the way. “Let the babies dance!” My sister Sweetie loved the way everybody was looking at her and started shaking her little ass with a big smile on her face. But I hated the music pounding in my ears and all those eyeballs watching me. There was no way I was gonna let loose and get on down. Instead, I did the two-step with my face fixed like I was sucking on a lemon. But it didn’t even matter, those drunk-asses still enjoyed the show. Sitting in a beat-up old chair by the window, Mr. Tommy, a regular, leaned back to watch my sister. He looked at her like she was a juicy piece of chicken and he was about to dig in. “Mmmm-mmm,” I heard him say to his brother, Po Boy. “She look real good.” Sweetie was eight years old.

I hated when Mama made us dance, but she did it all the time. I never knew why until one night when I saw Mr. Tommy slip her a couple of dollars right before she pushed me and my sister onto the floor.

Mama would do anything for a little extra cash. Anything, that is, except get a regular job. Her big moneymaking scheme, the one she came up with when I was seven years old, was picking pockets. Only she didn’t want to do the dirty work herself. Instead, she’d wake me up in the middle of the night and make me do it for her. I guess that was her way of giving me on-the-job training.

“Rabbit!” I heard her call the first time. I was asleep on a blanket on the floor in the bedroom Mama shared with her boyfriend, Curtis. Sweetie was beside me, curled up in a ball.

“RABBIT!”

I opened one eye and saw Mama standing over me. “Get your ass up,” she hissed, waving at me to follow her. She led me to the entrance of the living room and pointed inside. “See that?” she said. “They out cold.” The room was filled with leftover drunks from the night before. Mr. Tommy was asle

ep in a raggedy armchair by the bar with Po Boy knocked out beside him. Our neighbor Miss Betty was laid out, barefoot, on the sofa with her wig sliding off her head. In a chair by the card table was Mr. Jackson, the janitor from my brothers’ school, his head back and mouth hanging open.

Mama nodded toward Po Boy: “Go in there and pinch his wallet.”

“Huh?” I asked, confused.

“Take his wallet out his pocket and bring it to me. I’ll give you a dollar.”

I looked at Po Boy, then back at Mama. “What if he wakes up?”

“Chile, he ain’t waking up.” Mama took a step toward Po Boy and waved her hands in front of his face. “See?” she said. “He asleep.”

I stared at Po Boy; he had a thin stream of drool running from his mouth. Mama reached over and shoved him on the shoulder. His head fell forward, then jerked back. She nudged him again and he still didn’t move. “I told you he ain’t gonna wake up,” Mama said, satisfied.

What I didn’t understand was why she didn’t pinch the wallet herself. She was already standing right there, pushing and poking the man. What did she need me for? But I didn’t say a word. As scared as I was that Po Boy would suddenly open his eyes, find me digging for his wallet, and whoop my ass, I was even more afraid of Mama. One time she told me to get her a cup of tap water to chase back her gin and I didn’t move fast enough. So she made me bring her three switches from the yard and soak them in the tub. Then she braided them together and beat the dog shit out of me.

“Go on,” said Mama, pushing me toward Po Boy. “Go on and get it.”

Po Boy’s overcoat was hanging off his shoulders, making a puddle of cloth on the floor. I held my breath as I felt around for an open pocket and reached inside. When my hand touched the smooth leather of his wallet, I grabbed it and ran back to Mama, who was waiting in the doorway—I guess so she could make a break for it if Po Boy suddenly woke up.

Rabbit

Rabbit