- Home

- Patricia Williams

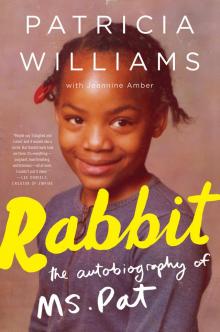

Rabbit Page 3

Rabbit Read online

Page 3

“Yes, sir.”

“It’s important that you understand that stealing will not be tolerated.”

“Okay.”

“Not tolerated at all.”

To make sure I was “receiving the message loud and clear,” he told me to stand up, put my hands on his desk, and bend over. Then he took his big wooden paddle and whooped my behind.

“Young lady . . .” SMACK

“At this school . . .” SMACK

“We . . .” SMACK

“Do not . . .” SMACK

“Steal!” SMACK SMACK SMACK

I suppose Mr. Dixon thought this was important information I needed to succeed in life. But bent over his desk with my ass on fire, all I could think about was food.

You learn to live with a lot of bullshit when you’re poor as hell: cockroaches crawling on your toothbrush, no running hot water for a bath, having to pack up all your belongings in trash bags every few months and move because your mama fell behind on the rent. But the one thing I could never get used to was being hungry.

After we left the liquor house and moved to the duplex on Griffin Street, Mama had to take care of us on her own. She didn’t have a job. Instead, she made do on a few hundred dollars in welfare and food stamps every month. But it was never enough. First the gas got cut off, then the electricity. One afternoon Mama made me go across the yard, to the apartment next door, and ask the old lady who lived there if I could plug an extension cord into her electric. That lady looked at me like she didn’t understand what I was asking for. “My mama need it for the TV,” I said, so she’d see it was an emergency. “The Young and the Restless about to come on.” The old lady shook her head, then took the cord from my hand, ran it through her side window and plugged it in. But we still didn’t have any lights. When night fell, we lit a pack of birthday candles and stuck them on the kitchen counter like itty-bitty table lamps. A birthday candle burns for about seven minutes, in case you’re wondering. That’s just enough time to make yourself a no-name ketchup sandwich and take your ass to bed.

Most nights I’d fall asleep thinking about food: Granddaddy’s homemade grits simmering on the stove; the chewy pizza they served every Friday for Free Lunch; Mercedes’s mama’s sandwiches dripping with Miracle Whip. I even dreamed about food I’d never had before, like McDonald’s, which apparently was too high class for us.

“Niggas don’t eat McDonald’s,” Mama said every time a Big Mac commercial came on TV teasing me with pictures of mouthwatering burgers that I could never have. One morning I was watching Mama’s broke-down set and the screen filled with a close-up of a Quarter Pounder. It looked so good, with the drops of water glistening on crispy lettuce leaves, I ran across the room with my mouth open to lick the TV, and damn near electrocuted myself.

As hungry as we were, I can’t say Mama didn’t try. She came up with all kinds of schemes to get us fed. One time she took us to the Curb Market late at night so we could dig through the dumpsters out back looking for anything the vendors had thrown out that wasn’t too rotten to eat. We found an old head of cabbage, some wilted carrots, and a couple of stale loaves of bread. Another time she took me and Sweetie out with her for hours in the blazing sun to collect aluminum cans from the trash people put out by the side of the road. When we were done, we took our trash bags full of cans to Davis Recycling across town. For all our hard work, all we made was fifteen dollars and forty-five cents. It was just enough for Mama to go to the corner store and buy some necessities: two packs of Winston, three quarts of Schlitz Malt Liquor, a package of bologna, a loaf of Sunbeam, a box of Saltine crackers, and two cans of Libby’s potted meat—which is a bunch of cow parts nobody wants to eat ground up to look like the kind of mess you find in your toddler’s diaper when the baby has the flu. The food, the beer, and almost all the cigarettes were gone by the next day.

Mama was sure the recycling man was ripping her off, so she decided to get even. “Lookie here,” she said to me and Sweetie the next week when we were out collecting cans. “Make sure you put some dirt inside.”

“What you mean?” I asked, standing on the side of the road with an empty Colt 45 beer can in my hand.

“Pick up some dirt and put it inside the can,” Mama repeated, like this was a regular everyday activity that any idiot would know. “Make sure you stomp it down and close it up so the dirt don’t fall out.” Mama figured this little trick would make the cans weigh more, and we’d get more money. But when we handed our trash bags over to the recycling man to get weighed, he picked up a bag and a pile of dirt spilled out. It looked like we’d spent the day at the beach.

“Lady,” he said to Mama, “you can’t pull that shit over here. I’ll pay you for these, but don’t come back here no more.” He weighed the cans, then subtracted 30 percent for the dirt and handed Mama eleven dollars and thirty-five cents.

“Damn crackers trying to keep us down,” Mama muttered to herself as we left. “Don’t matter how hard you work, no one gon’ give you a chance.”

By the time we got home that afternoon, we looked something sorry. We were sweaty, hungry, and covered in dirt. Our neighbor Miss Cynthia, who was sitting on her stoop, must have sensed the desperation because she called out to Mama, “Y’all going to church tomorrow, Mildred?”

“No, ma’am,” Mama answered. “I do my talking to Jesus at home.”

“You know,” said Miss Cynthia, “they got a real nice food pantry over there. They like to help folks out. Sometimes they even give you a little help with the rent. I’m just sayin’, with you taking care of all those children by yourself . . . Hell, I been over there to get a few things from the pantry from time to time, and I got a man.”

Mama told me and Sweetie to go on inside, then she sat down with Miss Cynthia to get the lowdown on all this food the church folks were giving away for free. I hate to say Mama was scheming on the Lord, but before she found out about the food pantry the only religion I heard about at home was when Mama told me I better pray to Sweet Baby Jesus she don’t whoop the black off my ass. The day after she talked to Miss Cynthia was a whole different story. Mama was up bright and early, telling all us kids to put on some gotdamn clothes so we could go to muthafuckin’ church.

Greater Springfield Baptist, a big red-brick building with white columns, was catercorner from where we lived. Every Sunday we’d see folks heading to worship: ladies in their good wigs, girls in pretty dresses, boys with hard-soled shoes and fresh haircuts. If Mama had known about the free food giveaway, we’d have found religion as soon as we moved in.

Mama told us to get dressed that morning, but she didn’t say “nice.” So we rolled into church looking raggedy as hell. We slid into the back row, Sweetie with her dirty flip-flops hanging off her feet and me in cutoff jean shorts and a pale green boy’s T-shirt decorated with a picture of the Incredible Hulk. I looked around and quickly discovered that this was not regular church attire. The lady beside me was decked out in a purple dress, matching purple shoes, and a big-ass purple hat with all kinds of feathers and leaves and flowers decorating the top of it. It looked like she was wearing a gift basket on her head.

At the pulpit the preacher, dressed in a brown three-piece suit and dripping sweat, was yelling at the congregation like we were a bunch of bad-ass kids. “God tells us in his Fifth Commandment to honor thy mother and thy father!” he hollered. “I said HONOR thy mother and father!” He held his Bible high over his head, like it was raining out and he didn’t want his hairstyle to get wet. “Now, brothers and sisters, what does it mean to honor your mother and father? Does it mean you gon’ run out and buy your mama a brand-new color TV set?”

Beside me the lady in purple started to laugh, her bosom, covered in baby powder, jiggling like a bowl of Jell-O. “Oh Lord, I’d like that!”

“NO!” yelled the preacher, his voice bouncing off the walls of the church and right into my eardrums. “The true meaning of honor has nothing to do with the giving and receiving of material goods. It�

�s about respect and obedience! Do you hear me? Respect and obedience. O-B-D-ence.”

It felt like hours that I sat there watching the pastor wave his Bible in the air and yell. After a while, I looked over and was stunned to see that my three brothers were all knocked the fuck out, sound asleep with their eyes closed and heads rolled to the side. How can they sleep through this scary-ass shit? I wondered. The preacher was hollaring about eternal damnation and the white-hot fiery furnace of hell. I was more terrified than the time I watched The Amityville Horror on Mama’s little black-and-white TV.

When the preacher was done yelling, everybody except my sleeping-ass brothers stood up to sing. His Eye Is On the Sparrow. Even Mama knew the words. And then—Praise Jesus!—it was finally time to eat. My brothers stretched and rubbed their eyes as we made our way downstairs to the church hall, in the basement. The room was filled with long tables and church sisters wearing white aprons over their Sunday clothes, dishing food onto paper plates: crispy fried chicken, turnip greens, homemade biscuits, and macaroni and cheese. “Thank you Lord,” I said, as I shoved a chicken leg into my mouth. “Thank you for all this good-ass food!”

After dinner all I wanted to do was lean back and take a nap. But Mama had other ideas. It was hustling time! She took me by the hand and dragged me over to speak to the pastor, who was standing near the doorway talking to the lady in purple and her husband, who was half her size.

“Look real sad,” Mama hissed at me as we walked over. “Pretend you is lost.”

When our turn came for time with the pastor, Mama spoke in a voice I’d never heard before, high and tight, like a little girl. “Pastor,” she squeaked, “I got five kids I’m taking care of all by myself.” When she said this, she pulled me to her chest and gently kissed the top of my head. Her tenderness startled the shit out of me, and I could feel myself go as stiff as a board in her arms. From across the room, my brothers were pointing at Mama and laughing so hard at her bullshit that Andre squirted milk out of his nose.

“We really struggling,” Mama continued, without missing a beat. “I sure could use a blessing.” The preacher looked down at me and then pulled Mama off to the side so they could talk in private. I watched him take her hands in his and the two of them lean forward in prayer. I don’t know what those two talked about, but as soon as we got home from church Mama had an announcement.

“We all getting baptized!” she said.

“Who?” asked Dre, looking up from where he was kneeling by the front door practicing his lock-picking skills.

“All y’all.”

“Why?” asked Andre.

“’Cause I said so,” explained Mama, cracking open a beer. “We joining the church. Now don’t ask me no more questions. Jesus don’t like that. Didn’t y’all listen to a gotdamn word the preacher was saying?” She raised up her hands as though she was testifying, only she had a cigarette dangling from her lips. “O-B-D-ence!” she hollered. “That’s how you niggas is gonna get to heaven.”

The next Sunday we got up, got dressed, and walked back across the street to church, where we all got dunked in icy cold water in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. After we got baptized is when Mama got invited to the pantry. It was everything Miss Cynthia had said it would be.

Sister Ernestine took out a cardboard box and started loading it up with rice, flour, powdered milk, a bag of sugar, Tang drink mix, three cans of sardines, and a jar of Jiffy peanut butter. “Thank you, ma’am,” Mama kept saying. “I’m just trying to feed my babies. That’s all I’m tryna do . . . Praise Jesus.”

“God is good all the time, all the time God is good,” Sister Ernestine answered. “Through Him all things is possible.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“God’s work done God’s way will never lack supplies,” she added. “Chile, I heard that on the TV.”

Greater Springfield Baptist Church was the first congregation we joined. But Mama didn’t discriminate. She thought we should go see what kinds of charity other churches had to give. Her baptism hustle took us all over town. We became members of Mount Zion Baptist, New Jerusalem Baptist, Bethel Baptist, Shiloh Missionary, Free for All Baptist.

One Sunday Mama even doubled up, taking us to two services in a day. I don’t know what the pastor thought when we all showed up to get baptized with our hair already wet.

Chapter 4

Angel in Leather Boots

Miss Thompson was my regular third grade teacher, but she didn’t teach me much of anything, unless you consider giving the side eye a skill. All my most important learning happened Monday, Wednesday, and Friday afternoons from one o’clock to 2:05. That’s when I went downstairs to a small classroom across the hall from the cafeteria to see Miss Troup for Title I remedial reading. Kids called it the slow class, but I didn’t care. I loved hanging out with Miss Troup. She was the exact opposite of my mother, quiet, calm, and patient. Plus she was the number one sharpest dressed teacher in the whole school. Miss Troup must have had a closetful of pastel-colored skirt suits and matching floral blouses, because it seemed like she wore a different outfit each day. She styled her hair in a big, bouncy press ’n’ curl and wore long fake eyelashes. But best of all were her boots: bad-to-the-bone, knee-length, brown leather with stacked heels, and always polished to a shine. She looked like she just stepped out of the pages of Jet magazine. Miss Troup—the baddest bitch at English Avenue Elementary—is the teacher who finally taught me how to read.

“Patricia, honey, just try to sound it out,” she said one afternoon, tapping the page with a bright red fingernail painted the color of a cinnamon Red Hot. We were sitting in her classroom with a book cracked open on the desk in front of us. It was hot and I was tired. “Just give it a try,” she said again. I looked hard at the letters. I knew they were strung together in words I should recognize, but none of it made sense.

Not everybody in my life knew I couldn’t read. Mama, for one, thought I could read my ass off. Every afternoon, she would pick up a copy of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution at the corner store. First she’d flip to the comic strips and put her face close to the paper, looking for numbers she was convinced were hidden in the hair or clothes or scenery of the cartoons. Like maybe she’d see a 4 in the background behind Charlie Brown, or a 7 in Hagar the Horrible’s beard. Those were the numbers she’d use for the fifty-cent bets she placed with the Numbers Man. The only other thing she got the newspaper for was to check her daily horoscope. But Mama had never finished elementary school and didn’t know how to read. Instead, she’d hand me the paper and ask me to tell her what it said.

“Sagittarius,” I’d say, looking down with my forehead wrinkled in fake concentration. Then I’d make some shit up: “This is NOT a good day for beating on your children. TODAY IS NOT A GOOD DAY FOR ANY TYPE OF WHOOPING AT ALL!”

Reading Mama’s fake horoscope was easy, but with Miss Troup reading took all my brainpower. Sitting beside her, I could feel the frustration rising up inside me. “Sound it out,” she said again. “Just take your time.” On the page in front of me was a drawing of a cat wearing a big-ass striped hat and red bow tie, holding an umbrella. What the hell? I thought. If the damn picture made no kind of sense, how was I supposed to figure out the words?

“I don’t know what it says,” I mumbled.

“Just give it a try,” she urged.

“I can’t do it.”

I put my face down on the desk, closed my eyes, and swung my legs hard, kicking the metal frame of my chair with the back of my heel.

Bang

Bang

Bang

Bang

I could feel the tears coming. I didn’t even know why I was crying. “It’s okay,” Miss Troup said softly, rubbing my back. “You’re doing fine.” I thought she was going to let me sit out the whole lesson with my face on the desk, the way Miss Thompson did in my regular class. But instead she told me to sit up. Then she turned her chair to face me, looked me in the eye, and said, “

Patricia, I’d like you to come by my room tomorrow morning before the first bell. Do you think you can do that?”

“Why?” I asked, worried. “Am I in trouble?”

“No, not at all,” she answered, gently. “I want you to come in early because I have a little something for you.”

Then she smiled at me, big and wide, with her cherry-red lipstick and Chiclet teeth, and I got the feeling that whatever she had for me had to be something good.

The next morning I splashed some cold water on my face, pulled on the musty jeans I’d been wearing all week, and took off running—past Mama asleep on the living room sofa with a Bumpy Face bottle on the floor beside her—and out the front door. I flew past Drunk Tony hanging out on the corner. “Girl, you gettin’ some ass!” he yelled at me, like always.

“Fuck you, Tony!” I shouted back, and kept on running. When I got to the school, I flung open the side door, ran up the ramp, and busted into Miss Troup’s room, sweaty and out of breath.

“Good morning, Patricia!” she said, looking up from her desk. She was wearing a peach-colored dress with a giant bow at the collar and her bad-bitch leather boots. “I’m so happy to see you.” Miss Troup reached under her desk, pulled out a blue nylon gym bag, and told me to follow her down the hall to the girls’ bathroom. We stepped inside and she started taking things out of her bag and setting them down on the side of the sink: a brand-new bar of Ivory soap, a pink container to put the soap in, a Tussy cream deodorant, a tube of Aquafresh toothpaste, a white washrag folded into a little square, and a brand-new toothbrush with a red handle, still in the wrapper.

“Patricia,” she said, turning to me, “these are your things.”

I looked at the items she’d laid out, then back at her, confused.

“They’re for you to wash up,” she explained. “I’m going to step outside and give you a little privacy. While I’m gone, I want you to use the washrag and clean your face and neck and under your arms, and put on the deodorant. When you’re finished, you can change into these.” She reached back into her gym bag and pulled out a bright yellow and white striped T-shirt and a brand-new pair of jeans. I’d secretly been hoping that Miss Troup was going to give me a pair of knee-high leather boots and a big curly wig. But a pair of stiff new jeans from Woolworth and a fresh top were almost as good.

Rabbit

Rabbit